This post was originally written for Oppositelock, but with the potentially impending death of Kinja user blogs, I’m reposting it here.

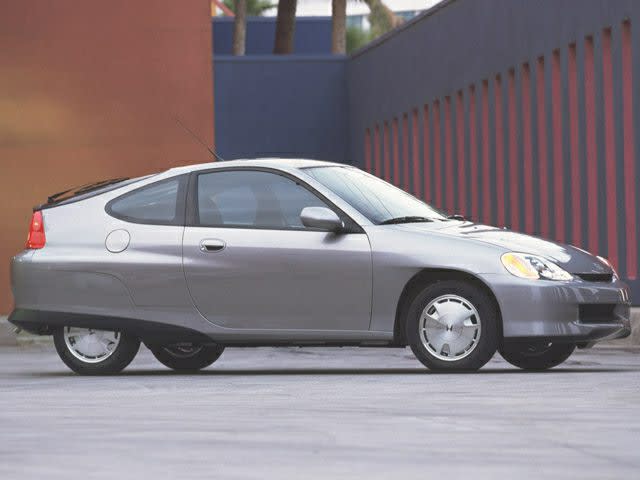

As a hybrid enthusiast who’s noticed quite a few questions about hybrids here on Oppo (as well as on Jalopnik), I thought it might be useful to write up a primer on hybrid technology, the various configurations of hybrid systems that are out there, and what all of that means.

So, there’s a bunch of different ways to classify a hybrid, but the two main ones consist of how much electric power versus internal combustion engine (I’ll abbreviate that to ICE from here on out) power is used, and how the ICE power makes it to the wheels (in both general and specific senses). Therefore, that’s what I’ll focus on. Also, I’ll primarily focus on hybrid electric vehicles (outside of heavy duty and motorsports applications, that’s all that’s in production), but I’ll talk about other systems, too.

In this first part, I’ll discuss classifications based on the degree of hybridization.

Micro hybrid

You’ll see some (primarily 2000s-era) writings occasionally referring to vehicles being “micro hybrids”. This is really an outdated term (I’m under the impression that Smart coined it to try to ride on the coattails of Toyota and Honda’s hybrid products), but it refers to two features that are still around to this day – ICE start-stop, and alternator cutoff. In addition, Mazda’s i-ELOOP system adds a large capacitor so that more energy can be harvested during braking.The reason that this term is outdated is because a so-called “micro hybrid” system does not propel the vehicle, and therefore is not considered to be a true hybrid. It does, however, provide fuel efficiency benefits, due to idle elimination, and only engaging the alternator during braking or when the battery voltage gets too low, reducing engine power demands.

Mild hybrid

A mild hybrid is the next step up from a “micro hybrid”, in that it can also assist the ICE in propelling the vehicle, making it a true hybrid of two power sources. However, a mild hybrid system is unable to propel the vehicle on its own, the ICE must be running to provide propulsion. These systems are usually designed to be retrofitted to existing ICEs and/or transmissions, and are usually parallel hybrids that operate through the gearbox. Fuel economy is improved over micro hybrids, as mild hybrids can recapture more energy and then use it to reduce engine load during acceleration or cruising, but because the electric motor cannot propel the vehicle alone, low speed efficiency isn’t as good as full hybrids.

Full hybrid/strong hybrid

A full hybrid or strong hybrid is a hybrid that is capable of operating solely on electric power, with the ICE not running. It is worth noting that, while called a “full” hybrid, full performance often requires the ICE (see the EREV definition for more on this). Many, many configurations of full hybrid are possible. Full hybrid systems are able to maximize low speed fuel efficiency by only using the engine when it’s truly needed – when power demand exceeds what the battery can supply, or when the battery is empty.

Plug-in hybrid (PHEV)

PHEVs are hybrids that are designed to have their batteries charged from the electric grid, to reduce the amount of fuel energy that is required to drive the vehicle over shorter distances. Typically, a PHEV will have a larger battery to accommodate this ability, as most hybrids without a plug have very short range (approximately 1 mile or less) without starting the ICE. A plug-in mild hybrid is possible (and Ferrari originally intended to sell the LaFerrari in that configuration), but I’m not aware of one being commercialized, so in practice, these are all at least full hybrids.

Extended range electric vehicle (EREV)

EREV is a marketing term used by General Motors to refer to PHEV products that have full power and torque delivery available when the ICE is off, used to market the Chevrolet Volt. Consider this a “full strength” hybrid, a step beyond the “full” hybrid. The obvious advantage to an EREV is that within the battery range, the engine will never need to start, meaning that a EREV can avoid fuel usage entirely in normal driving, whereas in lower-performance PHEVs, hard (or in some cases – I’m looking at you, Toyota Prius Plug-In – moderate) acceleration will require an engine start, using fuel.

BEVx

BEVx is a California Air Resources Board classification for a vehicle that has a range extending ICE, but that limits use of the ICE to approximately the same range as the all-electric range, and does not start the ICE until minimum battery level. This classification exists to provide a “limp home” functionality for electric vehicles that are unable to charge, while still counting them as equivalent to zero emissions pure battery electric vehicles for taxation purposes. Ultimately, this is the opposite extreme of hybridization to the mild hybrid – the range extending ICE is extremely limited in application and power delivery, and the resulting vehicle is primarily a battery electric, much like how the limited hybrid functionality of a mild hybrid makes it primarily an ICE vehicle that’s only helped by the hybrid system. The only BEVx I’m aware of is the US-spec BMW i3 REx, and the design of the BEVx standard has caused quite a few issues for owners of these cars.

Tomorrow, I’ll cover driveline configurations of hybrid vehicles, both in general terms, and detailing the common specific drivetrain configurations.